The poetry of stones

Added: 15 June 2019

Within ten minutes of our arrival at Avebury, as we were setting up our poetry corner in the chapel, a man, maybe seventy years old, asked me to transcribe a poem for him. His hands were shaky; he figured that I would write it better than he could. After we had finished, he told me he had written this poem, about threats posed by humans to the natural environment, as a sixteen-year-old, in a neighbouring village.

Our days at Avebury and Stonehenge repeatedly demonstrated the depth of appreciation that ordinary people have with the environments they inhabit, and the capacity of poetry to help them to articulate it. It felt like the hypothesis on which Places of Poetry was built – that poetry is a powerful medium for the expression of the relations between individuals, places and their histories – was being manifested over and over.

We experienced it again in a workshop for members of public-facing staff at Stonehenge. When asked by our poet-in-residence, Will Harris, what the place meant to them, each person expressed something thoughtful and personal. One spoke about the effect of mists rolling in of an evening and dissipating in the morning, another talked about solitary encounters with hares. And one man told how he had been working on the site when he received news that his father had suddenly taken ill. When this man returned to the same spot several weeks later, after his father’s death, he was overcome by a feeling of connection with his ancestors. Such, for him, was the emotional power of this place.

And we experienced it at a poetry-reading in Avebury, when we called for locals to read poems alongside Will. We had seven takers, spanning a wide age-range. They included published poets. They included also a National Trust archaeologist who had supported our visit, and had been moved to write her first poem since she was at primary school.

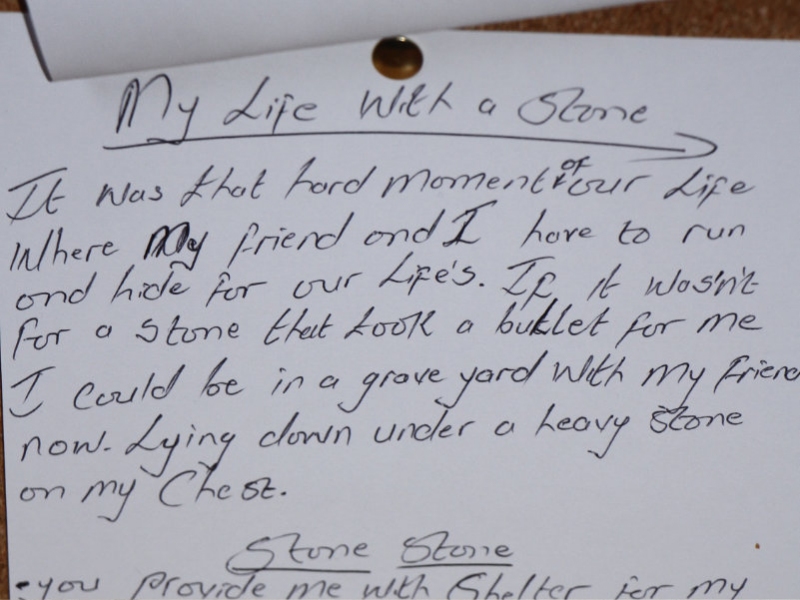

Our engagement with a group of recent immigrants from the Harbour Centre in Swindon was fascinating in other ways. These people were all awaiting decisions on asylum claims; how would they respond to Avebury? One man walked among the standing stones in the drizzle singing – beautifully – Persian songs. But stones held other meanings as well. The most moving poem produced in this workshop described how a stone (or rock) had saved the author from a bullet. His friend had not been so fortunate, and lay now in a grave, thousands of miles away, with only a stone to record his existence.

Search Poems